By Rebecca Filner, Head of Cataloging

Smallpox was one of the leading causes of death in 18th-century Europe, killing about 400,000 people annually and leaving many more disfigured or blind. Epidemics in major cities routinely killed 20% or more of those infected, and this case-fatality rate rose to 80% for infants.

Variolation, a process through which people were deliberately infected with mild strains of smallpox in an effort to shield them from catching a more virulent form of the disease, was first used in England by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu in 1721 and became increasingly common later in the 18th century. However, 0.5 to 3% of variolated patients still died of smallpox, and there was always the risk that a variolated person would infect others with the disease.1

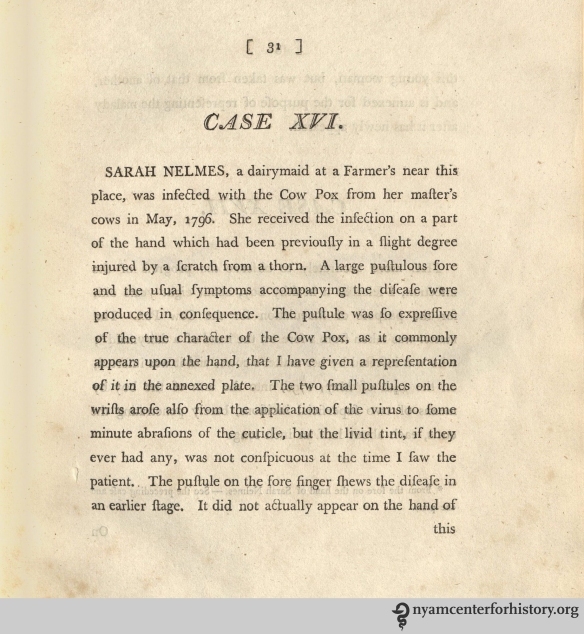

Enter Edward Jenner, an English doctor working in Gloucestershire in the late 18th century. Jenner was interested in testing the commonly held rural belief that dairy maids exposed to cowpox were no longer susceptible to the disease.2 He first heard this theory in 1770,3 and he began compiling case studies to test it in the 1780s and 1790s. On May 14, 1796, Jenner performed the first documented cowpox inoculation, taking a sample from a cowpox pock on the hand of a dairy maid named Sarah Nelmes and deliberately inserting the cowpox material into the arm of James Phipps, an eight-year-old boy. Phipps developed a cowpox lesion that healed within two weeks. When Jenner later exposed Phipps to smallpox through variolation, the boy was immune to the disease. Jenner was so confident that cowpox infection was a safe and effective method to prevent smallpox that he inoculated his infant son.

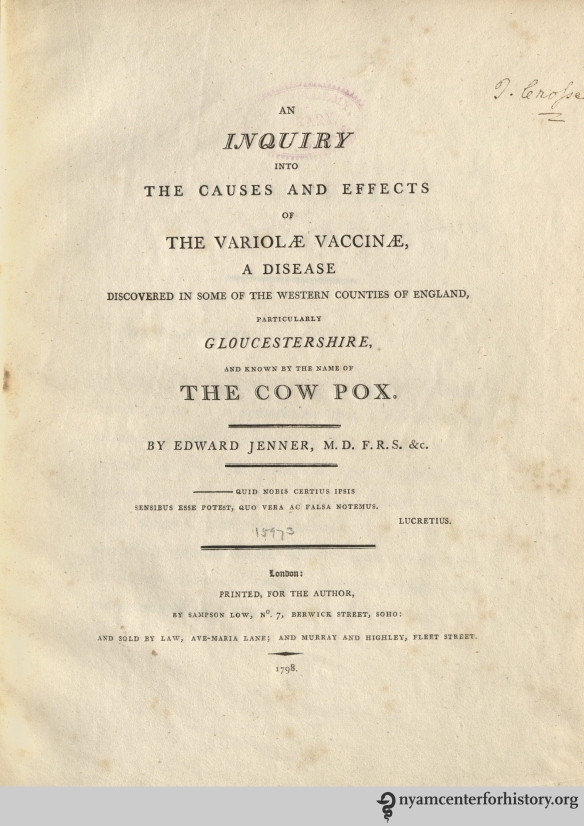

Jenner wrote a paper about his findings and submitted it to the Royal Society in 1797. The paper was not accepted for publication, however, because the reviewers found it had insufficient data. Undeterred, Jenner conducted additional trials and in 1798 published An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a Disease Discovered in Some of the Western Counties of England, Particularly Gloucestershire, and Known by the Name of the Cow Pox. He wrote three additional books on the same subject by 1801. Shown below is the title page from the first edition of the Inquiry, Jenner’s description of Sarah Nelmes’ case, and a detail from one of the color plates showing the cowpox on Nelmes’ hand.

The title page of the first edition of Jenner’s Inquiry, 1798.

Jenner’s description of Sarah Nelmes’ cowpox infection in Inquiry, 1798.

Color engraving of Sarah Nelmes’ cowpox pocks from the first edition of Jenner’s Inquiry.

Early reactions to the Inquiry from the medical community and the general public were mixed. A cartoon by the famous caricaturist James Gillray, shown below, plays on the fear that using animal matter on people would cause the patients to assume animal characteristics. Members of the medical community, especially those with investments in the practice of variolation, tried to discredit Jenner’s discovery or stake their own claim to it. Jenner had especially acrimonious feuds with two London physicians, Dr. George Pearson and Dr. William Woodville. Pearson even gave evidence against Jenner’s 1802 petition to the House of Commons for recognition of his work on vaccination.

James Gillray’s “The Cow Pock – or – the Wonderful Effects of the New Inoculation,” published June 12, 1802, by H. Humphrey, St. James’s Street. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

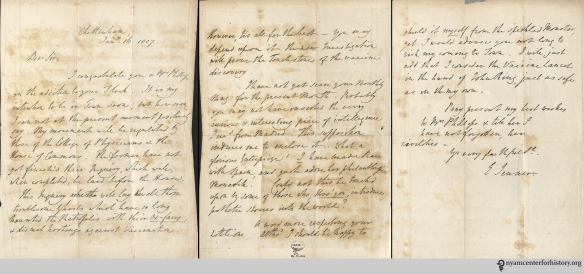

The New York Academy of Medicine holds a number of Edward Jenner’s autograph letters. In them, he rails against the misguided opposition to his discovery. On June 30, 1806, he writes to the Rev. Mr. Joyce:

“How wonderful that this horrid pestilence should at this time even have an existence in our island . . . A Physician from Copenhagen call’d on me today, and express’d his astonishment at an opposition to vaccine Inoculation, as by that means only the smallpox was completely extinguish’d in that City.”

Writing to a Mr. Phillips on Jan. 16, 1807, Jenner notes that the College of Physicians:

“[Has] not yet finished this Inquiry, which will, when completed, be laid before the House [of Commons]. This Inquiry will lay all those troublesome ghosts which have so long haunted the Metropolis with their ox-faces, & dismal hootings against Vaccination. However, tis all for the best – you may depend upon it the new Investigation will prove the touchstone of the vaccine discovery.”

Jenner also offers advice about his smallpox vaccine:

“A word more respecting your little one. Altho’ I should be happy to shield it myself from the speckled Monster, yet I would advise you not long to risk my coming to Town. I will just add that I consider the Vaccine Lancet in the hand of [Dr.] John Ring, just as safe as in my own.”4

In an autograph letter signed to Mr. Phillips, dated Jan. 16, 1807, Edmund Jenner discusses the ongoing vaccination controversy and offers advice for vaccinating Phillips’ new baby. Click to enlarge.

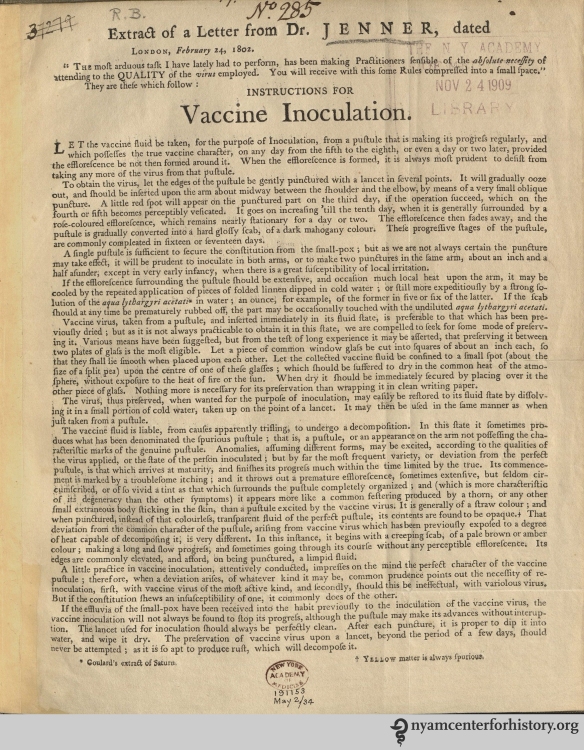

Despite some people’s doubts about the safety and efficacy of Jenner’s smallpox vaccine, there was great demand for cowpox samples to conduct vaccinations in England and abroad. Jenner and other practitioners in England sent dried cowpox specimens sandwiched between glass to Europe and the United States. The hand-colored drawing below presumably accompanied cowpox samples sent from England to America; the drawing shows the difference between cowpox pustules (on the left) and smallpox pustules (on the right) at 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 18-20 days after infection. Also shown below is an example of printed “Instructions for Vaccine Inoculation” from an “Extract of a Letter from Dr. Jenner, dated London, February 24, 1802.”

The New York Academy of Medicine holds this hand-colored drawing that shows the difference between cowpox and smallpox pustules at various stages of infection.

This broadside shows what kind of instructions were available for people interested in administering the smallpox vaccine.

The smallpox vaccine became more common during the 19th century, but smallpox epidemics continued to occur, at least partly because people did not yet fully appreciate the need for re-vaccination. In the 20th century, smallpox continued to plague third-world countries. Finally, a global eradication campaign organized by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1967 succeeded in eliminating smallpox. The last naturally occurring case was in Somalia in 1977.5 Thanks to Edmund Jenner’s research and his efforts to promote smallpox vaccination, one of the world’s most feared diseases is now a historical curiosity instead of an ongoing deadly threat.

References

1. These statistics are from Abbas M. Behbehani’s “The Smallpox Story: Life and Death of an Old Disease” in Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, v. 47, no. 4 (Dec. 1983), p. 455-509. Available online at http://mmbr.asm.org/content/47/4/455.long See also Stefan Riedel’s “Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination” in Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, v. 18, no. 1 (Jan. 2005), p. 21-25. Available online at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1200696/

2. The Jenner Museum gives a good summary of Jenner’s interest in cowpox as a way to prevent smallpox infection. See http://www.jennermuseum.com/vaccination.html

3. Behbehani, p. 468.

4. The quotations in this paragraph are from MS 1155 (Edmund Jenner, autograph letter signed: London, to the Revd. Mr. Joyce, 1806 June 30; first quote) and MS 59 (Edmund Jenner, autograph letter signed: Cheltenham, to [Mr. Phillips], 1807 Jan. 16; second two quotes.)

5. See the World Health Organization’s page on smallpox, available online at http://www.who.int/csr/disease/smallpox/en/

Pingback: Nursing Clio Sunday Morning Medicine

Pingback: Today is #GivingTuesday | Books, Health and History

Thank you for sharing such golden historic documents. These documents are priceless. Thank you.

Pingback: Dr. David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Early Republic | Books, Health and History